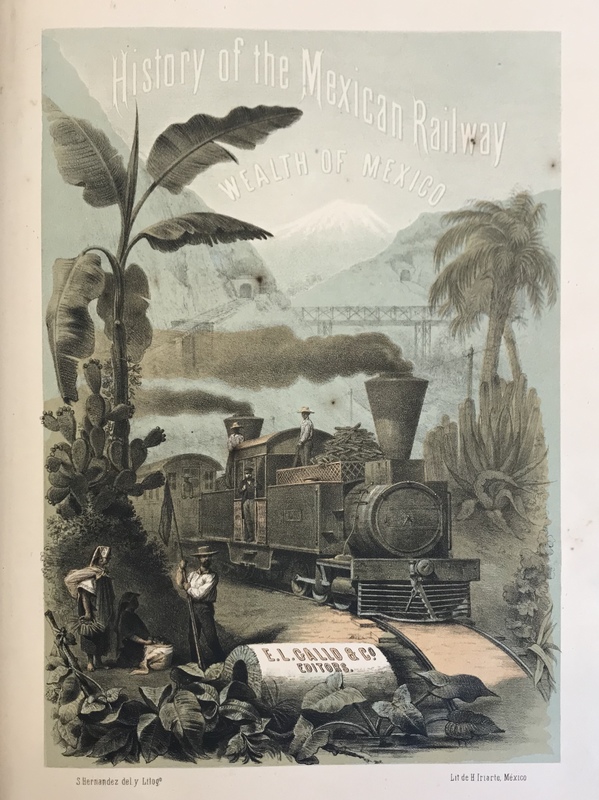

History of the Mexican Railway

Past the encyclopedic leather-bound cover, an exceptional multicolored lithograph fills the frontispiece. The Ajusco volcano stands tall in the background as a steam engine races over bridges and through tunnels, steam billowing out of chimneys, to reach the reader head-on. Indigenous farmers step aside as the steam engine chugs along the 250-mile inaugural rail line between Mexico City and Veracruz.

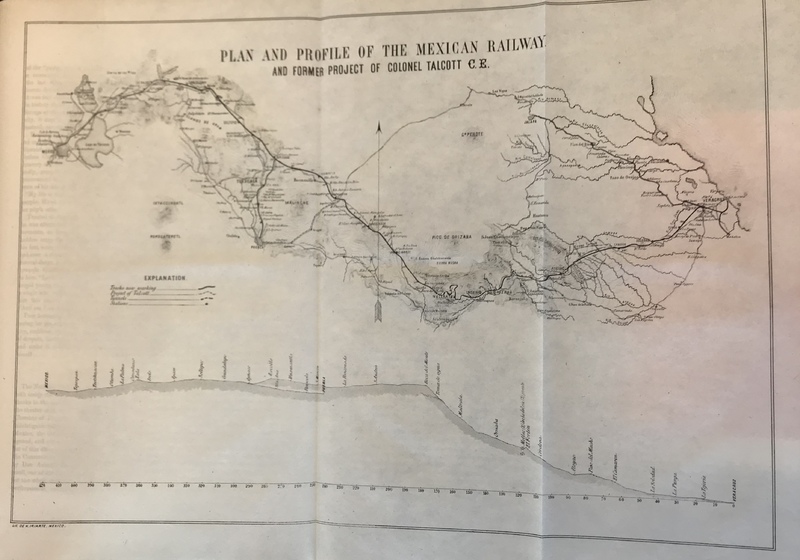

The History of the Mexican Railway details and celebrates the Mexican railway project of the late 19th-century. The book includes a trifold map, illustrating the sheer magnitude of the Mexican railway project. The track runs down the spine of the cartographic outline, with stations in each city. The header of the map credits Andrew Talcott, an American civil engineer,and reads, “Plan and Profile of the Mexican Railway and Former Project of Colonel Talcott.” From a birds-eye view, this map helps construct an image of the modern Mexican nation—sovereign and industrializing.

Chapters trace the route of the Mexican railway. Each city along the railway’s path serves as the subject of a chapter, beginning in Veracruz and concluding in Mexico City. Reminiscent of colonial ships’ content notices, Baz and Gallo produce pages of economic data within these chapters. The book recognizes each city’s resources and contributions to the national economy. They summarize imports, exports, populations, statistics of healthy civilians, agricultural production numbers, and recorded temperatures. With such records noting the region’s agricultural and mineral wealth, the realization of a Mexican railway system is implicit.

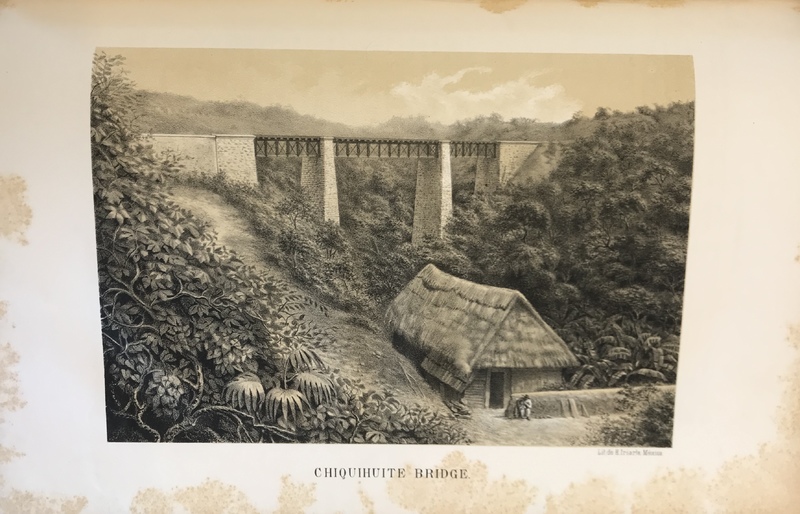

Lithographs advertise the numerous projects of the state. They illustrate the train stations, trestle bridges, tunnels, and ongoing construction projects along the national railway system. Counter to the dominant reading of these images, they also profile a consequence of modernization. People appear microscopic compared to the industrial projects they stand amidst. Iron and timber bridges breach the romantic landscapes, disturbing the land and villages. Indigenous communities must be sidelined in order for rails and ties to be laid. These observations become evident from the images, such as one depicting a straw hut in the shadows of an iron and stone bridge. While likely not intended, the artwork provides a non-binary perspective on Mexico’s infrastructural accomplishments. They celebrate the technological revolution and subsequent economic overhaul yet retain a criticism of modernity and change. Despite its quaint villages and rural indigenous life, Mexico, in the eyes of Baz and Gallo, can still be a modern nation with foreign investment. Though Mexicans wrote, printed, and published History of the Mexican Railway, foreigners are the desired audience. Between the inclusion of a foldout map with rail lines, formal documentation of the region’s resources,and lithographs unveiling Mexico’s infrastructural projects, Baz and Gallo market a commercial Mexico to foreigners.

—Daniel Meek