Cuba and the Fight for Freedom

Behind the sienna red binding, gold and silver embossing, and the comprehensive cover page notes, Cuba and the Fight for Freedom is far from a standard account of Cuban history. The 500-page book inaccurately markets itself as a general history of Cuba—a documentary of oppression, insurrection, and ultimately independence. In truth, James Hyde Clark, an American writer, presents his compatriots with a neocolonial manifesto disguised as travel writing and colonial history—a diplomatic, imperial voice whispers in the ears of readers.

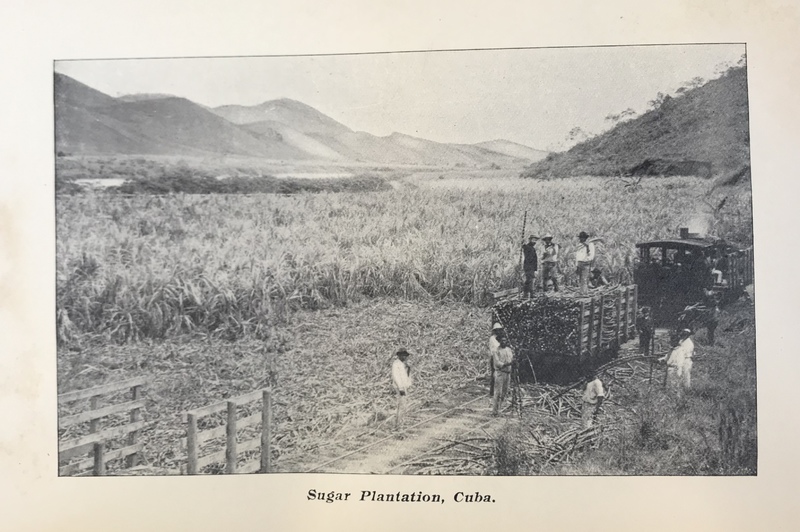

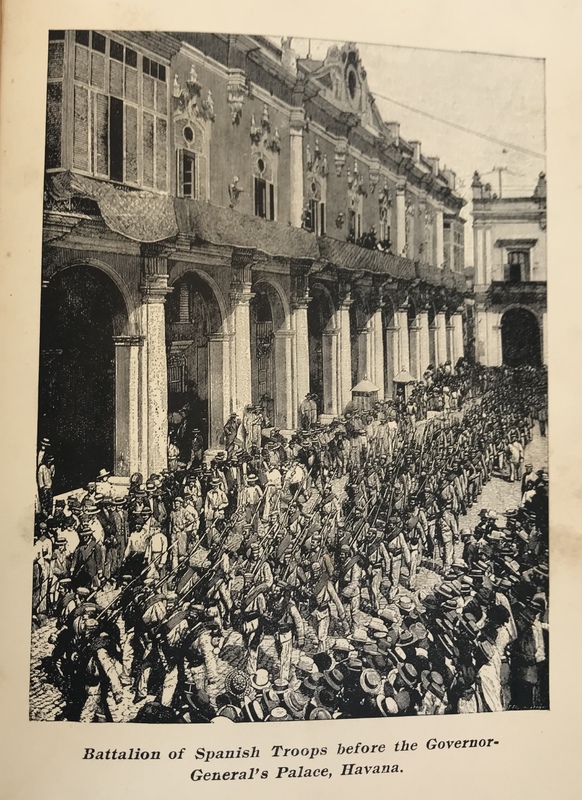

The profusely illustrated pages aptly reflect this masquerade. In one wide-angle photograph documenting the faces and farms of Cuba, a handful of sugar farmers stare back at the cameraman as they load a train car full of sugar cane stalks. The landscape appears fertile, welcoming American businesses. A subsequent illustration captures the island’s colonial past—Spanish soldiers mobilize in the early months of the Cuban War for Independence, reminding readers of Spain’s occupation and hostilities.

Clark’s preface serves as a platform to offer readers the truest sample of his intent. He launches into sympathetic pleas for American involvement on the island and espouses classical American neoliberal ideology. Clarkappropriates America’s struggle for independence and calls for the same revolution in Cuba—“Bunker Hill and Yorktown repeat [Cuba’s story] with reduplicated force” (5). Clark echoes the Founding Fathers in his appeal: “Tyranny exerts its sway by force, and force must be used to break that sway” (5).

In 1896, two years before the onset of the Spanish-American War, Clark disseminates a hawkish text to American readers and travelers. He writes,

“Surely every American heart must throb in sympathy with those of the Cuban patriots, who are fighting today for freedom and independence, just as our own ancestors did in 1776…Nor can one regard with indifference the character and disposition of a people who are our own neighbors, and who may one of these days become our fellow-citizens and their island a State of the American Union” (7).

Even more explicit comments litter the text as he refers to Cubans as “one day [American] citizens” several times. With pro-American and anti-Spanish rhetoric baked into the text, Clark brands Cuba and the Fight for Freedom as a tool for diplomacy.

Bookended on either side by Clark’s interventionist manifesto, the middle chapters unwrap the culture and customs of the Cuban people. Written for the American traveler, Cuba and the Fight for Freedom seeks to turn its readers into polymaths of the island. Clark instructs his readers on the four-day trip from New York to Cuba, where to shop, which tradesmen are the most respectful, how men and women should dress, the ‘orders of the day,’ and the best and worst housing accommodations. By the time Cuba and the Fight for Freedom hit the press in 1896, travel writing had displaced the travel lectures and oratory movements familiar to 19th-century America.[1] For more than a century, returning travelers shared their eyewitness accounts of foreign lands, acting out dramatic performances for a national audience.[2] A majority of Americans relied on these lecture circuits for entertainment, insight into foreign cultures, and an escape from their contemporary life. Since the readership existed, the introduction of travel writing destabilized the travel lecture platform—teachers, businessmen, military officers, and missionaries had a desire to read about and envision the ‘exotic’ lands of Latin America.[3] Clark’s text persuaded this diverse readership to sympathize with the Cubans and support Cuban succession.

—Daniel Meek