Brazil at the World's Fair: Race, Empire, and Brazil's Cosmopolitan Desires

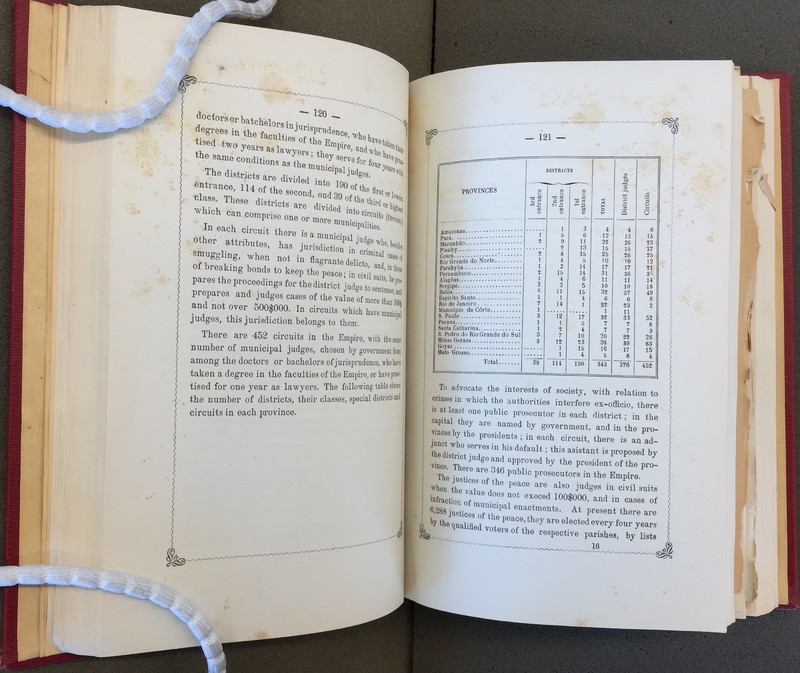

In May of 1876, Brazil sent a delegation to Philadelphia to participate in the World’s Fair, the first to be held in the United States. The delegates carefully curated exhibitions, which prominently featured Brazilian art, music, and literature, and presented Brazilian culture to curious onlookers. The delegation also commissioned this text, aptly titled The Empire of Brazil at the Universal Exhibition of 1876, a guide that introduced many aspects of Brazilian culture and society to North American and European readers. The approximately 500-page volume includes entries on Brazil’s education system, agricultural industry, naval infrastructure, and tables dedicated to demographic statistics (see images). The book’s discussions on such diverse topics reveal the racial and national ideologies that constructed an image of Brazil that the nation wanted to project to the rest of the world.

Brazil’s participation in the 1876 celebrations came at an important time for the Empire—Brazil recently emerged victorious from the Paraguayan War, though at tremendous economic, social, and political costs. As prominent 19th-century intellectual Sílvio Romero noted, the war opened up not only an economic crisis for the country, but also a crisis of identity. Following the devastation caused by the war, Brazilian elites began to worry about questions of national and cultural identity; they were especially concerned with the Empire’s international image. Indeed, being perceived as a “devasted post-war nation” did not bode well for Brazil’s modern desires. Participation in the World’s Fair and the publication of this book, then, provided means through which Brazil’s elite could curate and present to the outside world an image of their nation, one that would present the Empire of Brazil as a modern, progressive, and cosmopolitan country.

Throughout this book, the delegates make a clear effort to highlight the Empire’s many infrastructural achievements. Copious pages are devoted to discussing Brazil’s booming agricultural industry, for example. Highbrow culture is also emphasized: the book describes in great detail the many wonderful and well-organized libraries and museums founded in the nineteenth century. The book also discusses at length Brazil’s various education systems—public, university, military, and musical—and underscores how these “excellent” institutions were “highly effective” in educating productive members of society. Through these writings, the Brazilian delegation allowed their book to cultivate an image of the Empire as developed, cultured, and “civilized,” not unlike the many European nations that Brazilian elites so deeply admired.

The vision of national identity presented in the text, however, is built upon ideologically driven characterizations of the Brazilian population. Throughout, Portuguese and European contributions to Brazil are emphasized, whereas African and indigenous contributions are dismissed and occluded. The text’s discussion of indigenous populations only contributes to this narrative of national identity—not surprisingly, the words “Indians” and “savages” are used interchangeably, revealing the urban elite view of indigenous peoples as “backwards” forest-dwellers that contribute little to nothing to Brazilian civility. Additionally, the book’s discussion of slavery attempts to justify the practice by stating that slaves were treated “humanely” and “generously.” It continues: “Slavery, imposed on Brazil by the force of circumstances, since the first colonial establishments, will disappear in a few years more.” The Empire, keenly aware that their continuation of the practice looked bad to international onlookers who already abolished slavery, used this text to present itself in a favorable light.

Through this text, readers can glean various ideas about the Brazilian nation that its delegation sought to disseminate at the 1876 World’s Fair. On the one hand, the text reveals the Empire’s cosmopolitan desires, their desejos do mundo, as Mariano Siskind terms them, to integrate itself into the North Atlantic nations. On the other hand, the book reveals a problematic engagement with Brazil’s various racial and ethnic identities, one that eclipses black and indigenous groups with white and European ones. Livia Rezende calls this a “politics of exclusion,” one on which 19th-century narratives of national and cultural identity are based.

-Chris Batterman

For further reading, see:

Costa, Emilia Viotti da. The Brazilian Empire: Myths and Histories. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Guzmán, Tracy Devine. Native and National in Brazil: Indigeneity after Independence. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Rezende, Livia. “Of Coffee, Nature and Exclusion: Designing Brazilian National Identity at International Exhibitions (1867 and 1904).” In Designing Worlds: National Design Histories in an Age of Globalization, edited by Kjetil Fallan Graces Lees-Maffei, 234-262. Brooklyn, NY.: Berghahn Books, 2016.

Siskind, Mariano. Cosmopolitan Desires: Global Modernity and World Literature in Latin America. Evanston, IL.: Northwestern University Press, 2014.