Imperial Apologies: Understanding the Outsider’s Gaze in Transcontinental Diplomacy

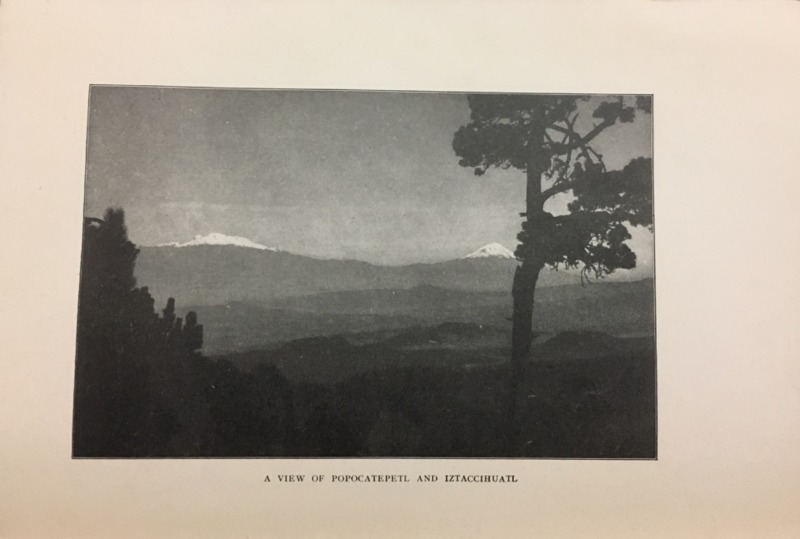

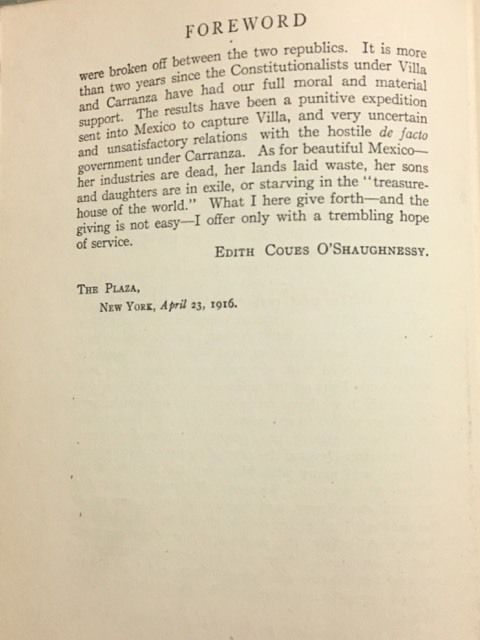

In 1911, Edith O’Shaughnessy began writing letters to her mother while she and her husband, an American diplomat, were stationed in Mexico during the years of the Mexican Revolution. What began as a picturesque image of Mexico’s beauty in her letters devolves into an apology, a condolence to the Mexican state lamenting the destruction of the same beauty O’Shaughnessy romanticized just three years prior. However, her remorse for the death of Mexico’s beauty is thinly veiled, as O’Shaughnessy’s pen proves prolific in demonstrating that American imperialism was not simply a man’s conquest in her text, A Diplomat’s Wife in Mexico.

A Diplomat’s Wife in Mexico, inscribed in gold lettering on the cover and external binding of an otherwise non-descript book, is emblematic of the identity that O’Shaughnessy emboldens. The title of a diplomat’s wife is not simply an accessory to O’Shaughnessy, but rather, one that she uses and exploits to enter male-dominated spaces of information control, gain access to classified information in the American Embassy, and validate her own credibility. After all, it is O’Shaughnessy’s undisputed credibility that permits readers to physically purchase and ideologically consume her product. The content of her letters range from the events of the Mexican Revolution to President Woodrow Wilson’s policies to what it feels like to be a woman in a foreign country during a time of political unrest. O’Shaughnessy’s keen sense of awareness allows her to complement access to male-domains of political information with a female understanding of and focus on domestic life in Mexico. It is at this critical juncture of female entry into foreign domestic life and access to elite male spheres of classified information that O’Shaughnessy makes her call for a civilizing mission in Mexico.

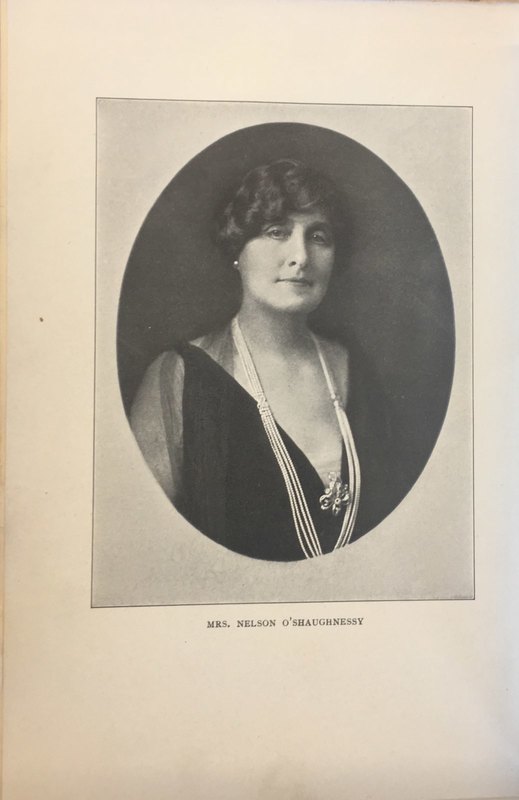

One instance that is particularly captivating in O’Shaughnessy’s letters is her portrayal of a poverty-stricken indigenous woman and child whom she encounters on a daily basis as the living, breathing embodiment of all the misfortunes of mestizo women. In this instance alone, O’Shaughnessy unequivocally calls for a civilizing mission of Mexico’s post-revolutionary state through a that privileges her and her “civilized” American audience. However, only those suffering who did not partake in the violence of the Mexican revolution warranted the pity and sympathy that O’Shaughnessy emotes in her letters and the civilizing obligation of the United States. O’Shaughnessy, however, omits any mention of Mexican women who were at the forefront of the Mexican Revolution, as to deprive Mexican women of any agency. O’Shaughnessy, herself, is pictured as the very epitome of civilization and sophistication, while the absence of any image of native people in O’Shaughnessy’s collection of letters testifies to her declaration of their unimportance.

O’Shaughnessy’s narrative of helplessness and sympathy compound the traditional narratives of Rudyard Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden,” except this time, it is a female pen that defines and divides the civilized from the primitive. O’Shaughnessy’s condolence to the Mexican state is deceptive. O’Shaughnessy’s apology for the destruction, violence, and death that occurred during the Mexican Revolution engenders a racist and classist obligation of the United States to civilize a deeply wounded Mexico and restore its beauty.

Citation: O’Shaughnessy, Edith. A Diplomat’s Wife in Mexico. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1916.

Author of the Exhibit Label: Omar Elsaai